WHERE TO FIND STORIES

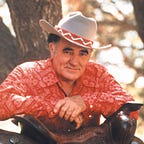

By Louis L’Amour

When my ship was at anchor in the Whangpo River at Shanghai a few years ago two women and three children used to come along side in a sampan to beg for food. There were many such sampans, but this family was clean, and the smallest child, a boy, appealed to all of us. One of the crew, a former gangster from Baltimore, was particularly attracted to him. Several years and a good many miles later, I made a story of the incident that was published in Story, and called “The Admiral.”

In San Pedro, I talked one night with a seaman with badly swollen hands, he was the sole surviving member of a ship’s crew, and had brought back the passengers in his boat safely in spit of storm, thirst, and endless days of sun. I made a story of that and called it ‘Survival.” Both of these stories were listed in O’Brien’s Index of Distinctive Short Stories

Another time I was struck by the similarity in sound between the words fighter and writer. The words rang a gong in my imagination, and as a result I turned out a story called “The Ghost Fighter,” where a champion hired a “ghost” to double for him while he was having a good time.

These are a few of the places where I have found stories. You may stumble across them as easily, not recognize them at the time, but later realize that you had a story angle. Stories are everywhere, and all the writer needs is to keep his ears and eyes open. Of course, the longer you work at it the more proficient you become in picking up the thread of a plot.

Not long ago I was sitting at a drug store fountain when a faded chap in the seersucker suit sitting nearby began to tell me a long-winded yarn. He had just returned from Memorial Park where he had been decorating the graves of his wife and brother, and it had started him remembering. His story wandered in and out among the swallows of beer he was taking, and had evidently been taking for a little too long.

At first it was just another story, and I wasn’t paying much attention, then something struck me, and I began to listen. His brother, a handsome young fellow, had shot himself some ten years before, was found dead in his room with a .22 rifle lying beside him. His wife had been killed in a car accident some years later. It all seemed like a couple of very ordinary tragedies until the pieces began to click into position, and to me at least it began to seem very obvious that the woman had murdered his brother. That story, when I completed it by filling in the details and pointing it a little, became “The Man In the Seersucker Suit.”

Beau’s Notes:

This was one of several articles that Louis first published in The Writer, a magazine billed in 1942 as “the oldest magazine for literary workers.” Seeing that this periodical was founded in 1887 and is still published to this day I would tend to take them at their word.

In “Where to Find Stories” Louis mentions four of his early short stories as examples, The Admiral, Survival, and The Ghost Fighter were all actual stories, the first two highly regarded. However, the last story, The Man in the Seersucker Suit is a mystery. References to this piece appear occasionally in Louis’s papers but I have never seen a complete copy. Until I do, I am going to assume that The Man in the Seersucker Suit is a figment of Louis L’Amour’s eternal optimism, a story planned but never actually completed even though he discusses it here as if it was a reality. This is an important aspect of his personality and his productivity as a writer. In his mind, once he thought of an idea it was done. Throughout his career he would discuss stories as though they were finished when he hadn’t even started. He pictured most of the work in his life as being complete from the moment he thought of it . even the work in this section that he never quite got around to.

One of the best places to find stories is in the human instincts. If you want to touch people and make them feel, get down to the bedrock emotions. The fundamental instincts were all have, dormant though some of them may be. The desire for a mate, for shelter, for food, for money — those are problems we all understand, and all of us can feel.

The instinct urge to seek shelter at night or from the cold has produced some of the best stories ever written. It is one of the earliest feelings man would have experienced, and when night comes he looks about for shelter, whether it be a suite in the best hotel, or the lee side of a fallen tree. O. Henry’s store “The Cop and the Anthem,” for instance, or Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous “A Lodging for the Night,” are noteworthy examples.

Great need will always produce a story. It does not matter what the need is. It can be for food, for shelter, for money to pay off the mortgage on the old homestead.

The instinct of fear, of flight is another convenient source of story material. The number of stores written about escape is legion, and it can be escape from anything: from prison, from gunmen, from enemy soldiers, from a trying situation, or from a man-hunting female. What becomes of the story depends on the writer and the particular slant he uses. The same general plot idea can be used for tragedy or humor.

William James once said: “Fear is a reaction aroused by the same objects that arouse ferocity. We both fear and wish to kill anything that may kill us.” In that quotation is source material for a hundred plots.

The hunting instinct is another fertile field for digging up plot material. Most of our hunting today is done for fun, but in many cases men still hunt men even though the weapons may be different and the hunt less immediately apparent. Jews are hunted in Nazi Germany just as Christians were hunted in ancient Rome, or slaves and abolitionists in this country. Richard Connell, one of the most proficient American writers of the short story, used that angle in his “The Most Dangerous Game.”

All stories are character stories, and the people, not words or plots, are his raw material.

Stories can be found wherever people are, and no writer should lose sight of the fact that in the last analysis all stories are character stories, and the people, not words or plots, are his raw material. The closer these people are to the foundation facts of life the more intense their stories, the more desperate their problems. Food to the average middle class American is just something that is eaten three times a day.

But food to the man in the gutter, to the man who walks along the dark streets, is not a simple thing. it is something that blots out everything else with a fierce craving. Hunger has been written about more than a few times, and probably the only place it was done well was in Knut Hamsum’s “Hunger.”

Once a nice lady who always lived in a warm home and ate well-prepared meals asked me why writers didn’t write about her kind of people instead of so many stories that were hard and violent. “All people aren’t like that!” she assured me.

Well, maybe not, but when they aren’t, in a great many cases their lives aren’t worth writing. It has been done, and well done, but the stories are more difficult to write and much harder to sell. People want stories about the dramatic, the intense. They want to be stirred, to be lifted out of themselves. Hegel once said that “Evil and conflict are mere steps toward ultimate good and serenity. Struggle is the law of growth.” Any fiction writer will use that for a general plot idea many times, with or without knowledge of Hegel.

Look for drama, for conflict, for where they are you will find stories. Some drama is obvious, striking. That kind will make the action magazines or the slicks. Some drama is obvious, striking. That kind will make the action magazines or the slicks. For more subtle forms of conflict you will go to the quality magazines.

There are various schools of thought on whether or not man is a gregarious creature by nature. Personally, I doubt it. Men live together because it is safer, more convenient, and easier, but they have never become quite reconciled to the idea. Strife will crop up, rivalry will grow intense, and the struggle for the simple necessities of life can bring men to the breaking point. Jungle law, fortunately for the writers, still prevails even if it has been smoothed over and made less obvious. The old emotions are still there, stirring beneath the surface, and ever ready to explode.

If you want to catch the interest of people, give them a struggle. Everyone likes to read the story of combat, of conflict, All sports are based on that idea, from badminton to boxing. In sport stories the conflict is born of the sport itself plus the personal equation. And the more intense and physical the struggle, the more people will turn out to see it.

But the struggle is everywhere, in every home and city and village, in every office and factory, in every school and club. It never stops and never ends, and so the person who looks abroad to far lands for plots, when he knows his own village, is more often than not wasting his time. For the conflict is at home as it is everywhere.

Of course, the far places have glamour. More often than not the struggle is more bitter. It is struggle in the raw. Along the Burma Road, in Libya or Russia, it is very apparent. In the Civil War of “Gone With the Wind,” or the westward trek of the Okies in” Grapes of Wrath,” the struggle is obvious. But it can exist anywhere. The most placid village can suddenly explode in a surge of violence and outrage!

Above all, a writer should keep up with the news of the day. Stories follow the news, or more often, precede it. More than once a fiction writer, watching the trend of events has written a story months in advance of the news. It is not so difficult to watch the way things are moving and guess just what will happen. This seems difficult, but many writers have done it and are doing it.

Fiction, in most cases, is more true than fact. acts are too bald. They present only the outline of what has happened, while fiction can reach down into the minds and hearts of the participants and tell their story. By far the best way to study history is to read historical fiction if you cover the field fairly well. It ceases to be an account of something past and becomes real and vital because personalities have been introduced.

There is no secret method of finding stories. There is no simple clue that can be given except to study people, and to keep your eyes open, and to listen. Stories are all around, and events that mean little to other people may mean a lot to a writer. In my own case I know, however, that I’ve never had a story idea given me by another person. People are always telling a writer they will give him an idea for a story. Usually he listens with patience and a vague smile. The difficulty is that few people, including beginning writers, have any idea what a story is. Very rarely the story they tell will make an incident in a longer story. But very rarely.

If you want story ideas I can only repeat, go back to the fundamental emotions and instincts and you’ll find a world of them. And watch the people around you. Not long ago I received a letter from a young lady living in a small town, and she was irked at being there. She wanted to write, and the town, she said, had no possibilities. Yet in telling me how dull it was it was she mentioned three situations rife with story possibilities.

In the course of a good many lectures given before high schools, clubs and universities I have often called attention to that charming story of a girl’s first date that was reprinted in the O. Henry Memorial Award collection a few years ago. It was called “Sixteen.” I believe that story is a perfect illustration of what can be done with a problem familiar to everyone. It couldn’t have been done better, and yet it called for no knowledge of the far places, just the simple excitements and feelings of a girl having an all-important date. Problems aren’t something one has to look for, and it is a problem that provides the story. What do you worry about? What does your wife, husband, or daughter worry about? Obviously, whatever it is, it is something that stirs them profoundly, and whenever anyone is stirred profoundly, you have story material. Fundamentally, all our problems are much the same, and if you worry about something, you can be quite sure there are many other people having the same worry, and others who have had or may have it. So, I repeat, get down to the bedrock of human emotions and instinct. It is a well that will flow endlessly with stories.